SURVIVIN' THE NIGHT

According to Esquire Magazine, circa 1975, Seattle is where you went to disappear. And it was in that year that I did so, hiring out into complete obscurity on the Milwaukee Road. The dark and damp of October was only more so on the Milwaukee. Obscurity permeated the Milwaukee Road in the Northwest. Few had heard of it, for the Milwaukee was out in the sticks, not next to the freeway, or on the waterfront, or in daylight. Trains departed the Coast in the dark, they rolled on the edge of town, not through the center like the ubiquitous Burlington Northern.

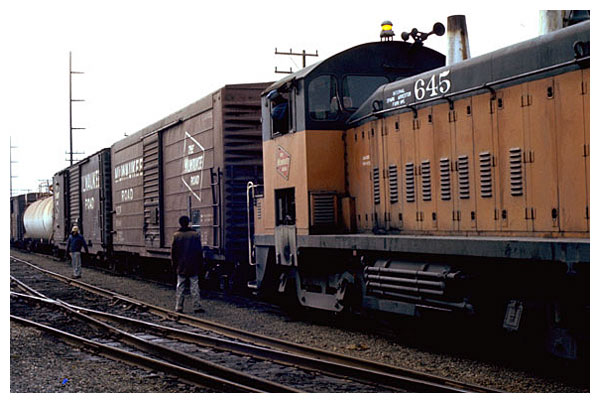

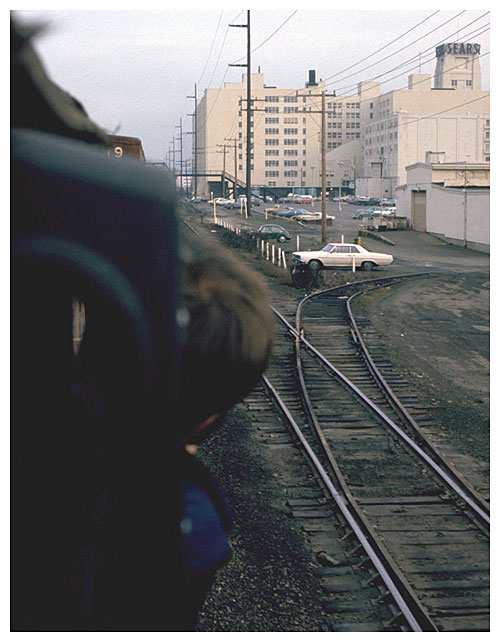

Denizens of Seattle Yard: Ron Cushway and Bobbilee WalstonThe tiny, Seattle "pocket" Yard hid in the dark behind the hulking Sears-Roebuck Building. There were few lights, unlike Super Stadium Flood Lighted Union Pacific Argo Yard, in full view of major overhead throughway, 4th Avenue South. Indeed, as if the yard office's location on back alley Utah Av. S. was not remote enough, the yard itself was named after Stacy Street, a rue nowhere to be found.

It rained on the B.N. & the U.P. too, but its effects were far more pronounced in MILW Stacy Yard, where gravel and spikes were unknown, where the mud hindered movement and formed the main connection between the "rail" and "ties." The muddy lead tracks and the absence of nightime illumination were two of our top three complaints whenever the Company safety officer conducted his occasional safety meetings. He was out of Chicago headquarters, and knew damn well that there would never be a dime for curing these problems. We were to deal with them with our inherent "professionalism". Then he would explain that accidents don't occur in the dark and the rain, they occur in daylight on sunny, dry days when you let down your guard (and he was right as I was to learn at B.N. Balmer Yard, a paradise on earth, safe and clean, yet imbued with a surprising lack of espirit de corps and ignorance of the car handler's craft). The third complaint, well that problem was part and parcel of the central dilemma of the Milwaukee Road: that it was one foot in the modern present and the other stuck in the Road's wooden axle past. That complaint was the tracks (numbers seven through fourteen) were too close, a very dangerous condition. Everyone, yardmen, yard clerks, yard bulls, yardmasters, car toads, each had stories about having to lie down in the mud if caught between those tracks. "Survin' the night" in this yard was not a sure thing. Not for old heads, not for hipnoid journeymen, and especially not for new hires like me. Two weeks of switchman classes at the Poodle Dog restaurant in Fife (with field trips to Tacoma, Van Asselt, and Seattle Yards) was poor preparation for this serious business.

Glistening Glue: Mud held the yard togetherI suppose we were lucky to get even that, formal education had not heretofore been part of railroad life. In what other industry would a midnight crew of three new hires be sent into the dark on their own, a crew not sure which lantern signal was used for backup or forward, or the foreman of which might have to search the ends of the locomotive to find that raised, white letter "f" that indicated "front." How sad to come to work on Saturday morning to find that new hire Jenkins had destroyed the House Lead, and Pig One, as well as toppling ten or so loaded grain hoppers across those tracks and Utah Av. S. And how lucky for me that my numerous transgressions avoided their disastrous potential. No wonder the railroad was in decline. Or was self-insured. There was no Allstate agent anywhere who wouldn't have fled that risk; not after seeing Bobbilee direct me to let fly five tri-level loads of Cadillacs that were instantly converted into 75 luxury lemons as the racks collided with a standing cut of loaded grain hoppers. Yes it is true that the "object struck suffers greater damage then the object striking" but this particular contest was not really fair; on impact those Caddies jumped the full length of their chains before slamming back down in clouds of dust. And for what, so that we would avoid "sawing" a switch? Surely there were many more hours of factory labor building those Cadillacs at risk then the extra minutes lost by shoving rather than by kicking . But then that was big picture thinking. And the big picture was not our problem, it was Trainmaster D.F. Galipo's, and General Yardmaster Bernie Johnson's. For our problem was simple, "survivin' the night."

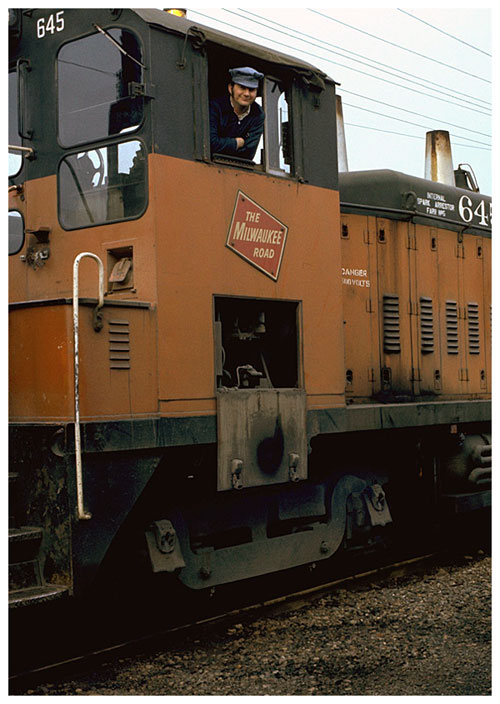

Tacoma Extra Engineer Rick CanadyIn my time in Seattle Yard, Woody Merchant was the highest seniority yardman, with a 1941 date. Even on the daily mark up board, the senior yardmen had regular jobs; Woody was foreman of the 6:30 a.m. job. His son Craig, followed me in seniority. I was the most junior in my hire-out class, Craig the most senior of the class behind me. I don't know if Craig was casual about work because he came from a railroad family, or just because he was natural at the moves. Tall and lanky, fast and agile, he was also artistic, skilled at jewelry and handcrafts. Rick Skirvin, who followed Craig, was a hipnoid rail from the Milwaukee in Kansas City; Rick was good, he knew the job, even as he learned Seattle Yard. I, however, am a slow study; but once I get it, I get it well. So I studied survival, learned safety from the book, and watched and listened. I didn't bother myself with whether the Harlowtown "shorts" were kept in track five, or the Sears and Sand Lot spots in track one. I was too busy stepping on knuckles, not draw bars; "palming" switches; and getting on and off equipment with the trailing foot, period, no exceptions, ever, always wear your seat belt.

The Hulking Sears building and Engineer Rick Canady

On that fateful night, I had had enough and needed rest. And I knew that Rick wanted to work. I laid off on the call for the 11:59 job. So instead of being pin puller, Craig filled my job, field man, and Rick was pin puller. I marked up the next afternoon, and that's when I learned what happened. Just after his dad Woody had come to work, Craig ended the shift in a medivac helicopter. As usual, Bernie Johnson had not given the 11:59 job a "quit," they always had to work to the "nuts" while the morning shift old heads sat in the lunch room, drinking their coffee and waiting for an engine. And that was when Craig Merchant, field man, ran after a boxcar that had been kicked too hard to clear alley track ten or eleven. When he caught up to the car, with its high hand brake on the leading end, he climbed up the OUTSIDE end ladder, not the inside end ladder. And that was when he was scraped off the side by a car on an adjoining track, and when he fell under the wheels of his car, and when he lost his arm and his leg. The Road would pay Craig's medical bills, buy him artificial limbs, and stand to be sued. But they would not fix the yard. For you see, "professionalism" is what let's you survive the night.

COAST DIVISION

SEATTLE YARD- Survivin' the Night

- Puget Sound Barges

- Switchin' & Trampin'

- Flat Switching

- Black River Yard & The P.C.R.R.

- Road Extra Board

- Tacoma Roundhouse

- Tacoma Junction

- Joint Line: Superiority of Trains

- Joint Line: Automatic Block Signals (ABS)

- Mainline: Othello

- Mainline: Extra 194 West

- Mainline: Extra 156 East

- Mainline: Beverly Depot

- Mainline: Columbia River Bridge, Boylston Tunnel, Renslow Trestle

- Mainline: Snoqualmie Pass

- Mainline: Cle Elum

- Mainline: Work Trains and Wreckers

- South Line: Rule 99 Territory

- Burlington Northern Pacific Division Third Sub: Centralized Traffic Control (CTC)

- Portland Trains

- Hoquiam Turn

- Tacoma and Eastern Railway (12th Sub): Mineral Turn

- Tacoma and Eastern Railway (12th Sub): Morton Local

- Olympic Peninsula (14th Sub): Port Angeles to Portland

Join the Milwaukee Road Historical Association and MilWest